Southwood, A Memoir

Molly and Rex

When I was a boy, I stole a yo-yo from a market near my home. I was 10 or maybe 12, though certainly not a teenager as those years were reserved for reckless behaviors of another sort. I didn’t lack for anything really; deprivation did not motivate my shoplifting. I was just a boy, selfishly taking something I wanted and did not have.

My impulsive desire for that colorful toy blinded me to the possibility of any consequence, especially pursuit by a store clerk. I seized the yo-yo, ducked under the shopping cart corral, and bolted to the parking lot outside. At the far end of the lot, I glanced back only to see a man wearing an apron coming my way.

For my getaway, I ran down Ponderosa Road, which in those days dead ended perpendicular to Fairway Drive. Fairway intersected with our new subdivision, known as Parkhaven. You entered this area by going left onto Rainier Avenue. My home sat halfway along the street at the top of a gentle rise. My brothers and I and other boys from the street played endless games of catch and football here, in front of our house, where the pavement leveled out.

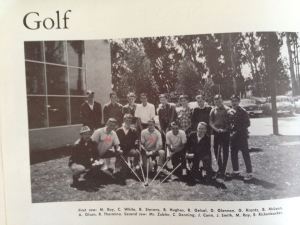

If you went straight on Fairway you continued into the larger area of Southwood to which Parkhaven belonged. The homes were older and surrounded the Southwood Elementary School. West of the school, the neighborhood nestled against the uneven boundary of a private country club where, as a teenager, I would work as a caddy and learn to play golf.

I attended Southwood from the 4th through 6th grades and, because it was California, we learned drills for both fire and earthquakes. For a fire, you evacuated the building, while for an earthquake you stayed in the classroom and hid under your desk.

The school had single story buildings connected by concrete corridors that were open to the air but covered to protect us from the rain. We played kickball during recess periods on an asphalt area adjacent to a grass field. At the end of recess a teacher would ring a stout hand held bell. It had a wooden handle and a bronze casing. Its clanger could pierce the hubbub of 200 or more grade schoolers at play. When the bell sounded, students were required to freeze in place, unmoving and silent, until being allowed, one class at a time, to walk in a behaved fashion to their rooms.

Lunchtimes were not so strictly monitored. Southwood did not have a cafeteria. Some children went home for a meal where moms from the 50s awaited them. Others brought sack lunches and wandered to the far corners of the playground, the boys separate from the girls, mingling only when one or the other got attention by showing off. Once, a girl named Pamela caused a commotion behind the backstop of the dusty baseball diamond by lifting her skirt to show some of the older boys her underpants.

To the south of Ponderosa Road, where I ran from the clerk, St. Veronica’s Catholic Church sat perched upon an island of asphalt. In 1956, when we moved to the suburbs from San Francisco, our neighborhood was so new that its only direct connection to the church grounds was a dirt path through scrubland over a makeshift footbridge that crossed an unnamed creek. On Sunday mornings, a pilgrimage of Southwood Catholics drove several miles in order to arrive at church from the opposite side where the roads were paved.

More undeveloped land continued behind our house on Rainier. In those days, an abandoned shed and fields were surrounded by a ring of pine trees. In years to come, Ponderosa Road would be extended, and a modern elementary school would be built on this property. A public playground would replace the Southwood classrooms.

My best friend, Chuck, lived four doors down from me. Together, we shot bows and arrows, built forts, and played games of hide and seek with other kids from the neighborhood in what seemed, in our boyhood, a forested preserve.

The creek that bisected the scrubland by the church flooded most winters. Often we tromped home with pants muddied to our knees, much to the consternation of our mothers. Usually, our dogs accompanied us. Chuck owned a mutt named Rex with a shaggy, rust colored coat. We had Molly, a black spaniel mix. Rex had a rascal’s love for wandering and female companionship. He would hump on Molly even though she had been spayed. He never wore a leash. He always returned from his amorous escapades, until finally, one day … he didn’t.

Molly’s demise occurred in our teen years. She’d never been trained properly and wouldn’t heel. Once we started exploring more distant environs, she stayed home. In her declining years, we confined her to our mediocre sized backyard with a doghouse tucked into a dry spot under the porch. My father became emotional when, eventually, Molly had to be euthanized. At some point she developed tumors and her back yard purgatory came to an end.

Little Boxes

My family was Episcopalian, which seemed to me a diluted version of the Catholic experience. This was due in part to the pomp of Latin Mass and stained glass windows at St. Veronica’s that soared upwards, I’d supposed, toward God or heaven.

Our church, St. Elizabeth’s, had a small congregation and a humble chapel, ¼ the size of St. Veronica’s. It sat across the street from a strip of small businesses, a gas station, the Post Office, and the Southwood Market where I’d run off with that yo-yo. The chapel and grounds have since converted into a real estate agency. But back then, all of this was north from Ponderosa, just a short walk away along Fairway Drive.

We were not devout Christians. My idea of prayer was limited to the success of sports teams I liked, namely the 49ers and Yankees. Furthermore, I can’t recall ever seeing my older brothers, Tom or Jim, or my dad at church. Still, at St. Elizabeth’s, I served as an altar boy with my brother closest in age, Earl, who we called Butch due to his scrappy personality.

We attended Sunday school under the tutleage of Father Barbour. This occurred at the behest of my mother who insisted we be confirmed. My reward for confirmation, in addition to the possibility of a saved soul, was a small medal engraved with the dictum, “I am an Episcopalian.” Following confirmation, mom loosened the reins on our spiritual upbringing and declared that church was optional. So, of course, I stopped going.

Surely, I was not being very altar boyish on the day I skedaddled toward the safety of home with a stolen yo-yo clutched in one sweaty palm. Safe neighborhoods and conformity were the primary design attractions of tract home developments in the 50s. The post WW II suburban expansion featured uninspired homes, one like the other that, nonetheless, created a comfortable homogeneity. Everyone was white skinned in our neighborhood, though a sprinkling of Mexican-American families did live in the older parts of Southwood.

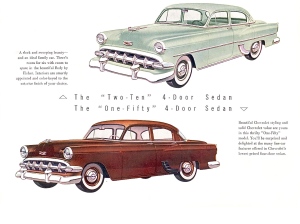

My parents owned a two-toned, 1954, 4-door Chevy, the car in which I would learn to drive come the early 60s. Mom and dad voted Democratic, preferring the blue collar appeal of the dull and doomed Adlai Stevenson to Dwight Eisenhower’s military cachet.

In the 50s, television was black and white with just three networks. A patriarchy of journalists reported on the news with poker-faced sobriety, softened only by the dry wit of Huntley and Brinkley. The Pandora’s Box of multiple news channels that we have today, which blasts strident noise along with questionable objectivity, had yet to be opened. However, social upheaval awaited. It would be facilitated, to some extent, by the blandness of the environment parents provided my generation. Norman Rockwell was about to meet Peter Max. But that was still a few years away.

I can recount six houses in a row on Rainier with identical floor plans to ours. They were three bedroom, two bath homes with a large picture window on the 2nd floor overlooking parked cars and the neighbor’s picture window across the street. One afternoon, I had to trudge in front of this gauntlet of observatories with my father in tow. He needed help walking as he had drunk too much whiskey at a barbecue hosted by another family further down the street.

Each of these homes had a brick stoop leading up to a hallway, living room, dining area, and kitchen. At one end of the hall, carpeted stairs led to the three bedrooms above the garage. I shared a room with brother Butch until Junior High School, when Tom, the 2nd oldest boy, got married and joined the Navy.

The houses all had stucco siding painted pale shades of brown, green, or blue. Stucco was a style popular to the 50s, cheaper than wood but durable, nonetheless. Each house had a rectangle of lawn out front, edged perfectly against clean sidewalks, but the yards were treeless in those days, adding to the overall ambient sterility.

The identical designs helped make these well built tract homes affordable. Later in the 60s and 70s, when the first generation of Southwood children left the nest, these simple floor plans would be remodeled with additions to expand the living area. Such improvements attested to the original quality of construction. The homes were representative, I think, of the Little Boxes made famous by the folk singer Malvina Reynolds and her peer Pete Seeger, though, perhaps, not so “ticky-tacky” as some.

It was to the room I shared with Butch that I fled with my purloined yo-yo. The store clerk apparently conceded the pusuit to my younger legs, for I never faced anyone’s wrath for the theft. Once home I tossed the yo-yo into the nether land under my bed, where only dust bunnies, my mother, and the odd sock dared to go. I don’t know if one of my brothers thought “finders-keepers” and kept it or if my mother tossed it away thinking it discarded. Whatever, I never saw the yo-yo again.

Two Bits

My dad smoked unfiltered Camel cigarettes, a pack or more per day. His favorite drink was an Old Fashioned, made with Jim Beam whiskey. He kept the cigarettes and drink ingredients, bitters and maraschino cherries, in the kitchen pantry. This was little more than a narrow broom closet by the door to the backyard. We also fed our cat there. Tup Tim or Tuppy, as we called her, was a Seal Point Siamese, a slinky, crosseyed cat who would cuddle with me under the bed sheets at night. Dad’s bourbon, honey colored, sat next to Tuppy’s kibble and Molly’s dog biscuits. Occasionally, dad would allow me to sip his drink. It tasted fiery, unpalatable to my youthful tongue. But I loved the cherries and he would sometimes let me have one.

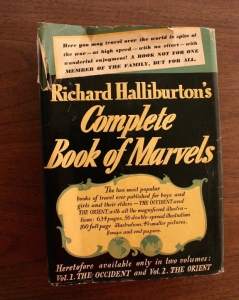

Inside our front door, against the wall between the hallway and living room, was a maple bookcase quite memorable to me for storing a collection of National Geographic magazines and a copy of Richard Halliburton’s Complete Book of Marvels. I read this book cover to cover many, many times, and scrutinized the fold out maps from the Geographics. My imagination soared with adventure fantasies, the first fuel for a restlessness that powered me to escape the predictability of the Southwood environment.

Otherwise, I did the normal things of boys my age. During the summer months Chuck and I often walked uptown to Grand Avenue and the public library. We enjoyed the horse and dog books by Thomas C. Hinkle. We also spent hours each day at Orange Memorial Park hanging out near the Rec Center, joining other kids in games of tetherball or chess and checkers.

In the evenings, our family watched television. Mom often worked the swing shift at a hospital in San Francisco. So dad heated and served meals she had prepared in the afternoon. He was already a determined drinker. He’d arrive home each evening with a half pint of Jim Beam, which he would empty, at a reasonable pace while we watched our beloved cowboy shows of the time: Gunsmoke, Wagon Train, and The Rifleman. My generation grew up on these simple morality tales from the frontier. Before long, though, the Vietnam debacle would intrude upon my peer’s delusion that happy endings were an American birthright.

On many of these evenings, Dad fell asleep on the couch. Later, I’d understand that he prepped the night’s half pints with a couple of drinks at a nearby tavern before coming home. Butch or I would awaken him and, if necessary, help him to his bedroom. Once, he whispered, with whiskeyed breath, a promise to quit drinking. But he never did.

Chuck and I played little league baseball for the 12-Mile House, a tavern from another neighborhood, though Orange Park was our home field. When dad and mom came to the games and it was my turn to bat, my father would yell, “Two Bits!” If I got a hit, I got a quarter, which, looking back, seems a better deal than I got from two years of Sunday school at St. Elizabeth’s. Chuck would go on to be a successful pitcher for the High School team. I gravitated toward golf, attracted, I think, by the solitary nature of that sport.

Behind the bleachers of the ball field, on the other side of a parking area, and beyond a row of grand eucalyptus trees, railroad tracks ran north to south. There, an aquaintance, one of the Ming boys, tried to hop a slow moving freight train and lost a foot. We didn’t know their family well so the shock was not as visceral as it might have been otherwise. Evidently, the tracks are now gone, replaced by a bike trail.

I never tried anything so reckless, well, not for several years anyway, but I did, along with friends Mark and Jay continue a pattern of misbehavior by throwing rocks through the cafeteria windows of Los Cerritos School. This was located on the other side of the tracks just up the street and catty-corner from the baseball diamond. We did this several times. Our M.O. was to attend a dance held at the Park’s rec center on Friday nights. We’d leave early, tossing rocks under the cover of darkness before heading to the Foster Freeze in Southwood for burgers and ice cream. We must have bragged about our cleverness for, at last, another boy squealed and the police came to the Southwood school.

They removed us from class. We were interviewed one at a time in the Principal’s office … well, sort of. The other two boys went before me and my one on one never materialized. The truth of the matter unfolded quickly behind a closed door. Before I could even consider utilizing my supple skills for deception and not implicate the others, Mark and Jay were receiving praise for their honesty and contrition. I never learned where this left me in the eyes of the investigating officer but I felt a minor injustice had been perpetrated upon me.

Nonetheless, we were punished equally: along with the shame of having to confess the crimes to our parents, we were scheduled to meet with what I suppose was known as the Juvenile Officer at the police station. All three families gathered there for a somber lecture on the thin line between good and bad. We were ordered to pay a fine for the vandalism. I don’t recall the exact amount but it could not have covered the damage. I imagine the school’s insurance paid the true cost.

Kids, particularly boys, steal and find mischief with a variety of irrational acts. I was no exception. Impulse control is not well developed in young men. Occasionally, as with the unfortunate Ming boy, this leads to serious misfortune. Dogs die and fathers, both familial and clerical, sometimes disappoint. Later, as I wound my way through the fog of teenage consciousness, the Vicar of St. Elizabeth’s forfeited his calling by running naked through the Southwood neighborhood. It was not the same Father Barbour who had presided over my confirmation, but a successor who had lost his way.

Three Ways to Pick Up a Tarantula

Growing up, we vacationed every summer in Yosemite National Park. Mom and dad would awaken us kids before dawn and pack us into the backseat of the family car. Usually, we slept for half the drive, awaking to eat breakfast in the central valley town of Tracy. Afterwards, our anticipation rose with the altitude as we drove east through the arid foothills and climbed the twisting roads leading into the Sierra Mountains.

My sister Mary was born in February of 1960 and that summer mom stayed home with the baby. Dad, however, maintained the Yosemite tradition by taking Butch and I for a week. We were allowed, for the first time, to bring a companion. My best friend, Chuck, couldn’t go, so I invited a boy named Greg.

Greg lived in the older part of Southwood, a few streets north of Parkhaven, on Hillcrest Court. I never learned what his parents did for work but evidently they encouraged him in the natural sciences. Greg had a curious, eccentric mind, and would later make a career as a biologist with the Idaho Fish and Game.

Science texts crowded his bookshelves at home.They were well worn much like my tattered copy of Halliburton’s Marvels. He collected insects and showed me how to douse them with chloroform and pin their fragile thoraxes onto a cardboard display. He also had a thriving ant farm, garter snakes, and a pet tarantula. In fact, when we were fifth graders, he brought his spider to Southwood Elementary for show and tell.

The day must have been wet, for recess occurred outside our classroom under the shelter of the corridor’s coverings. Other students clustered about Greg to look at his tarantula, safely ensconced in a gallon jar with air holes punched in the lid. Or … so we thought. Somehow, the lid was off and Mr. Spider, larger than our hand, black and hairy, was corraled between the fence posts of our spindly 5th grader legs, unpredictable as a nightmare.

I expect that the tarantula’s terror equaled ours and he did what spiders do in such situations: he ran. Eyes rolled, faces contorted, and voices shrieked but for the most part, our cohort of 11 years olds froze in place, pinned by fright as securely as the insects in Greg’s collection at home.

More cringing occurred when the spider sought the first dark place it could find to hide, which was the inside of Greg’s pantleg. Up it scurried, leaving a discernible mole’s hump in its wake until Greg, with heroic poise, coaxed the tarantula back down to his shoetop. He cradled its abdomen in his fingers, then returned it to the jar and secured the top.

But that happened when we were 5th graders. By the summer of ’60 we teetered on the cusp of high school. We were still young boys but we were no longer little boys. Dad let us wander independently in Yosemite. His passive caretaking leant a sense of maturity to this vacation that seemed absent from previous visits.

As usual, we stayed at Housekeeping Camp in tent cabins that dotted the curve of an S-turn made by the Merced River. Each unit had a wood floor with canvas sides and a canvas roof that extended as a canopy out front.

Greg and I lived on birdsong and woodsmoke. We skipped rocks on the river and prowled the forest floor. Greg taught me about owl pellets, the regurgitated bits of indigestible prey. We floated on air mattresses down the Merced along with brother Butch and his friend. Our destination was a swinging bridge, several miles downriver, where dad awaited with the car to haul us back to camp. Our shoulders burned and peeled in the summer’s sun and freckles danced on our noses.

Dad behaved himself. Yosemite’s wonderland enchanted us all. Each evening after dark we’d sit around a fire in front of our tent, watching flames consume time, mesmerized by the moment, and the prospect of endless tomorrows like today.

That fall, I started high school. With Mary’s arrival, all the attention that had been focused on me, as the youngest of four boys, dissipated in the glow of her infancy. I became less visible and welcomed the change. Soon, I spent more time at the country club adjacent to Southwood. I found work there, and spending money, and new friends from outside of the neighborhood.

How I Learned to Swear

I lived just a few blocks from the high school. Each morning, Chuck and I headed east on Ponderosa Road and cradled textbooks, heavy as boulders, under our arms. We dodged the bustling traffic on El Camino Real and, once across, climbed the fence behind the school’s auditorium.

Tumultuous times lay ahead for my Class of ’64. At the height of the Cold War with Russia, John F. Kennedy defeated Richard Nixon for President of the United States. Soon, though, The Bay of Pigs Invasion dimmed the glow of this election. And in May of ’61, an accident to a classmate dulled the sheen of our own freshman promise. Ron Martinez, a gifted athlete, broke his neck when diving into the shallow end of the school swimming pool. ADA accommodation was still 30 years away. He abruptly vanished from our lives.

I didn’t play school sports as a freshman. I did, however, start golfing with fervor. I spent time at a public course located on the infield of the Tanforan Race Track, located just a couple of miles south of our neighborhood. Fueled by candy bars and soft drinks, my brother Tom and dad patiently taught me the game.

Back home on Rainier Avenue, heavy equipment cleared the fields behind our house. A new elementary school would soon be added to the burgeoning school district of South City. As a freshman, I spent afternoon hours alone whacking a golf ball back and forth on the leveled dirt. It was there, on that moonscape of excavated ground, where my introverted personality first felt the rapture of solitude.

Golf became a way for me to engage with nature. And, the San Francisco Bay Area had numerous courses to explore. Dad occasionally dragged me along with his regular group. They played at first light each Saturday morning on the Harding Park Muni next to Lake Merced. Tom, upon returning from the Navy, had professional aspirations. Soon, his connections with other local professionals led me to work as a caddy at the California Golf Club.

The Cal Club, an exclusive 300 acre unincorporated enclave, bordered the entire western edge of Southwood. An eight foot high cyclone fence, topped with barbed wire, protected its perimeter. Yes, it was a golf course, prosaic in purpose, but immaculate in a design that evoked the finest parklands in America: simultaneously cultivated and wild. The quiet of its forested grounds beckoned and access lay just steps from my home on Rainier Avenue.

The limited, private membership left it vacant for much of most days and my book wormy imagination nested in the feathery aeries of its cypress trees. The contours of the natural routing dovetailed with my memories of Yosemite’s meadows and forest trails. I became adept at scaling the defensive hurdle of the fencing, and claimed the preserve as my own, even if belonging was beyond the means of Southwood’s middle class families.

At the caddy shack, I met a colorful collection of characters. Exuberant swearing, petty gambling, bragging, competitions for everything from spitting to jobs, this male milieu hardened the shell of my personality. But inside, I remained soft, a scrawny timid boy and for a time the smallest of the bunch. I kept my head down, cautious to a fault for fear of breaking the shack’s protocols. I was called Little Smitty in deference to my better known brother.

The permanent full time caddies lived an existence that bordered on homelessness. These men were peers of my dad’s, who, for whatever reason, had not enjoyed his luck in negotiating the difficult years of the ’30s.

One fellow, Norm, lived out of his car. My soon to be new best friend, Red, who was a year ahead of me in school, called him the “aqua velva man.” Norm reeked of the popular after shave lotion. Evidently, it served as his “dutch shower.” Another man, Arnold, babbled indecipherable phrases and we called him “hooski pooski” for this was often his answer to a reasonable question. There was Lou, Lefty, Lippy, Whitey, Ridgerunner, Dickie Smith, and more, characters right out of the pages of The Grapes of Wrath.

Eventually, I ascended the caddy ladder and became a shop boy. This position had unique benefits. First of all, Red and I entered the inner sanctum of the pro shop together. We bonded during this period of self-discovery as confidantes, privy to the little dramas between the elite members and the professional staff. We forged a friendship based on trust as sacred as the secrets we shared.

In exchange for cleaning the member’s golf clubs and running errands, we received the best “loops” and could play the course after work. Also, when Red and I became old enough to drive, members would toss us keys to have their cars washed. Cadillacs, Lincoln Continentals, XKEs, Cobras, and even Ken Venturi’s Aston Martin were trusted to our care. Yet another compensation, which appealed to our teenaged opportunism, lay in coercing the regular caddies to purchase alcohol for us on the weekends.

After dark, Red, me, and other friends would park along the first fairway and chug cheap vodka from a milkshake cup mixed with Dr. Pepper or Coca-Cola.

Once, a suspicious constable foiled our evening’s plan. The officer must have seen us turn up the private drive to the country club, waited, and then followed us with his lights off. For, just as we were about to imbibe, with all the evidence in hand, the bright glow of a flashlight struck our eyes. That night, I was the driver, using the family car, our 54 Chevy.

We were given a warning and driven home to our parents. As usual, dad would have been knee deep in his evening half pint. Together, we walked the several blocks back to the car, reflecting the incident when I was younger and assisted him up Rainier Avenue. This time, however, Southwood shrouded us in darkness and he didn’t stagger. The irony was lost on me but, well … there you have it.

In the autumn of my junior year, current events again chipped away at the innocence of my generation. The Cuban Missile Crisis saw our country and Russia taunt each other with ICBMs. The craze of fallout shelters peaked among the well to do. But our mundane suburban lives in Southwood moved along above ground. Red and I played on the high school golf team. Our friendship grew. We united as prisoners of the twin adolescent tyrannies: acne and bungled romances.

No one ever “came out” from the Class of ’64, which means there existed a lonely handful or more of gays or lesbians among us, trapped in the constrained sexuality of mid-century America. They played sports along side us; they attended the balls and proms; they joined the same clubs, and went on the same field trips. And we never knew or, perhaps, could even understand the depth of their loneliness or the “otherness” that we unconsciously reinforced day by day.

As a senior, I disassociated myself from school culture, choosing instead to hang out at the Cal Club with Red, for he had taken a job there in the Pro Shop. The number one song that year was The Beatles’, I Wanna Hold Your Hand. And, just as my friends and I began the final lap of high school, JFK’s assassination occurred in Dallas, Texas. Unsettled by this event, we nonetheless hurtled toward a future teeming with rock and roll, drugs, and war.

Double, Double Toil and Trouble

I began college at San Francisco State, a commuter school on the south edge of the city. I promptly wasted most of my savings on an iridescent red Chevy that looked cool but kept breaking down. So, I dropped out after the first semester. My parents co-signed on a loan for a brand new 1965 Volkswagen, which, in those days, cost $1968.00. That price included three years of financing. I went to work at the Cal Club, taking a job vacated by Red as caddie master.

I lived at home in Southwood, with the understanding that I would return to college. I worked six days a week managing the caddies, the golf carts, and the driving range. I received $400 a month, plus lunch. Tuition in those days cost $52 per semester. Accordingly, an industrious kid could conceivably pay his own way and I never questioned that expectation. These days? Not so much. High school graduates need a benefactor or they likely will exit college with a hefty debt.

The “double, double toil and trouble” of Vietnam brewed throughout the early ’60s. For several years, televised media ignored the covert escalation of the war. Sitcoms and western dramas soothed a populace inured to the labored rationale of our involvement in Southeast Asia. But the body bags of young American soldiers, kids my age, began to accrue. Upon my return to school in the fall of ’65, a rising tide of anti-war sentiment gathered itself and would soon flood colleges across the country.

I tumbled along, playing on the college golf team. I enjoyed the travel and saw many new courses in northern California. But the thrill of competition faded when I took my first summer job in Yosemite National Park. The summer of ’66 marked the beginning of a new direction for me … thereafter, whatever happened in between one summer and the next, be it exciting or not, would be experienced in suspension to the desire to return to the park. The flying buttresses of its granite walls captivated my imagination. They seemed to hold aloft the very sky, and there, my dreams floated.

During the school year, I worked nonchalantly on an English degree. I studied poetry through the school’s Creative Writing Program and learned about the economy of words and the rhythm and cadence of sentence structure. But becoming a poet was a ludicrous aspiration, even though I succeeded in acting the part. I was no longer the little boy who stole yo-yos, but I was still a thief, not averse to “borrowing” personas in the attempt to find myself. The unintended consequence was that it introduced me to an outspoken and quirky crowd comprised of artists and writers. I envied their authenticity; their comfort with Bohemian urbanity.

Meanwhile, my little dipsy-doodle of starting and stopping school left me vulnerable for the draft. Student deferments flucuated monthly depending upon the war’s ebb and flow. At its height, there were 500 American fatalities per week. Then, in 1967, Red got drafted. The immediacy of my predicament and a sense of powerlessness could not be denied.

Like many young men of the time, I lost faith in our leadership. Those who made the rules could not be trusted. After one more season, I stopped playing golf. It seemed out of touch with the broad rebelliousness of the times. I began smoking cigarettes and experimented with recreational drugs. I joined protests against the war. Eventually, I burned my draft card and resolved that, if necessary, I’d seek asylum in Canada.

The madness of Vietnam revealed itself with dispiriting events. My Lai, the Pyrrhic Victory of the Tet Offensive, and Kent State surprised even the staunchest supporters of the war. In due course, The Pentagon Papers unearthed the depth of deceit perpetrated upon my generation. And revelations continued to and beyond the ignominious fall of Saigon in 1975.

But that would come later, and I’d take no joy in having rejected the values of those years. Meanwhile, I continued to skate around conscription with a tenuous student deferment. I landed jobs in Yosemite for three consecutive summers, finding sanctuary in its pine forests. I started a fourth there but quit abruptly when my dad got sick.

I let my curly hair grow long. I moved out of the Southwood house and into an apartment in San Francisco with an artistic freckled strawberry blond Catholic girl. We lived the hippie lifestyle of drugs and rock concerts, incense and innocence. We clothed ourselves in the thrift store chic of the times: raccoon fur coats for her; bell bottoms and neckerchiefs for me. We danced to The Doors at The Fillmore Auditorium and The Moody Blues at the Avalon Ballroom. We attended “Be Ins” at San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, where local groups such as The Jefferson Airplane and Country Joe and the Fish performed free of charge for thousands.

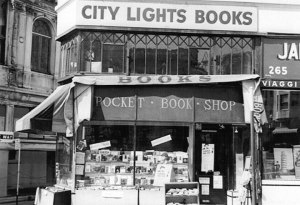

Inevitably, capitalism’s vulgarity wilted the ’60’s Flower Power. Still, we shared what was perhaps its peak of glory from 1968 to 1970. Marijuana was cheap, universally $10 a lid, roughly the equivalent of an ounce of weed. I stayed stoned most days, regardless if I were working or in school. We lived on Laguna near Union in the Pacific Heights neighborhood. I’d wander across Van Ness Avenue to North Beach, stopping at Vesuvio’s Cafe, which sat across the alley from City Lights Books. I sipped coffee and scribbled in a notebook at the bar, a pseudo poet, composing desultory verse.

Above the nexus of Columbus and Broadway, Grant Avenue climbed west toward Fisherman’s Wharf. In the afternoon, I played chess at The Coffee Gallery. Outside, drug hustlers prowled the narrow sidewalks, harbingers of the commercialism that would engulf the era. They’d bump shoulders and whisper, “Acid, mescaline, hash?”

Paying for living, of course, got in the way of all this bliss. I took a job working the graveyard shift at the Post Office, while continuing with school. My sleep suffered. I became a mediocre student, a bad employee, and an ambivalent boyfriend. Paranoid and irritable, I medicated myself with cigarettes and pot but this only served to make me crazier.

Then, in December of 1969, my girlfriend and I watched live the first Selective Service Draft Lottery. I received a safe number and no longer felt encumbered by school. Our romance ended when I spurned my education and moved permanently to Yosemite.

I shed the costume and other affectations of the struggling writer, sold my car, and departed for the mountains with few possessions. Meaning in life became for me a question of where to be, not what to be. I took work outside of the hubbub of Yosemite Valley, at the Wawona Hotel near the south gate of the National Park. I blended into the quiet of its community, savoring again the comforts of solitude. There was still much settling to come and acceptance of who I was. But, I was on my way …

Jimmy

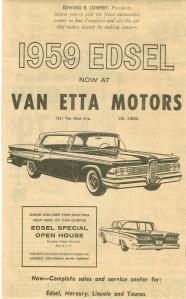

Throughout my youth, dad worked at Van Etta Motors, a Lincoln/Mercury auto dealership in San Francisco. He managed, what was called in those days, the body and fender department. One weekday, my mom and I rode the bus into the city’s downtown. She must have had an exceptional appointment, for I was left with dad at his place of work. The unusual circumstances notwithstanding, dad took me in tow.

Dented cars filled the repair bays of the cavernous garage where he worked. Arc welders sprayed sparks into the air. Dad warned me to not stare at the glow. He guided me to the quiet of his office, away from the bustling work floor. Calendars of naked women hung on the wall. At these, too, I tried not to stare.

Soon, we went to a nearby cafe for breakfast. A counter, fitted with stools that twirled, faced the kitchen. We sat, my dad and I, amidst the mechanics and car salesman from auto row. Everyone knew dad and called him Jimmy. I learned, that morning, the meaning of a ‘short stack’ and covered my pancakes with syrup. Dad sipped coffee and smoked.

His history was all broad outlines with few details. Early on, he had been orphaned along with his sister Florabelle. For unknown reasons, they were separated and raised by strangers. We heard tales that he played sandlot baseball, hopped trains, and lived as a hobo. This would have been the 30s, during the Great Depression. Somehow, he migrated as a young man from Oklahoma, where he’d been born, to Madison, Wisconsin. He was working there in a movie theater when he met my mother, a nursing student.

They married and the older boys, Jim and Tom, were born in the midwest in ’36 and ’40. By then, World War II loomed and dad found work as a welder in the shipyards of San Francisco. This critical wartime occupation deferred him from active military service. That is how the Smith family came west.

Dad provided for us, working eight to fives year in and out until the four boys left home. We enjoyed opportunities that had been denied to him when he was a child. He was a gentle man, short in stature with the rippled forearms of someone who worked with hand tools. He enjoyed Texas Rasslin’ from the 50s and 60s. On Saturday afternoons he would make a bowl of chili heaped with crumbled saltines to watch the matches.

His wandering Okie genes had merged with mom’s, which came from the stock of German dairy farmers. She had a foundation, whereas the rickety scaffold of dad’s youth toppled under the weight of alcohol. He died in 1969. Mary, as a little girl, witnessed the worst of his unraveling. The united response among us boys, who missed much of the downhill slide, was wiseacrery for his haplessness.

Mom survived, even thrived, you could say. Following dad’s death, she moved with my sister, first to Napa, California where she worked at the state hospital. Then, after I’d married and left the country, she bought a home close to the south gate of Yosemite. She lived there alone after retiring and later claimed that those were the happiest years of her life. Mary remained a companion for mom. Eventually, both returned to the home of mom’s birth in Wisconsin. My sister still works as a librarian for the city of Milwaukee. Mom passed away in 2007. She was 91.

Toward the end, many years after my visit to dad’s body and fender shop, he would be fired from his job. His workmates of many decades fell away. He soon found employment as an insurance adjuster. But this would not last long. One day, while driving home, he could no longer discern the colors of traffic lights. His liver was failing. If there was any grace in the matter, it is that he went in short order from being fully employed to being dead.

Following his death, we discovered a cache of empty liquor bottles in the crawl space under the house on Rainier Avenue. These were mostly cheap bottles of gin and vodka. Probably, dad had vowed to stop drinking. In reality, though, he had no inclination to do anything other than drink himself to death.

The family convened at a funeral parlor on El Camino Real, located on the outskirts of our Southwood neighborhood. The parlor, fittingly, was directly across the street from one of dad’s favorite haunts, The Fairway Tavern and, for which, mom spewed derisive commentary.

We chose a simple pine box and cremation of the default variety. The ashes would be scattered at sea by the proprietors of the crematorium. There would be a showing for dad but, as best we could tell, few showed. There was no memorial service or eulogy, though we did mourn with well wishers at the house on Rainier. But few existed or cared of those who still knew dad. The relatives were all on my mom’s side back in the Midwest. Mostly, it was just the six of us, mom and his legacy of children, sheltering our confusion with ritual.

We were an unemotional lot. This is just the way it was. Rootless and uneducated, the arc of dad’s life was destined to have a modest horizon. Its pinnacle would be in finding a place that was safe and predictable for his children, a place he’d never known as a child, a place that neither he nor I would inhabit for long: a place like Southwood.

Postscript

This began as a writing exercise. But memoir, I’ve learned, is like a trapdoor: once you trigger the mechanism you don’t know who or what will be waiting at the bottom when you land.

Writing about my youth made me aware of a misplaced resentment for dad. I have a renewed appreciation for his parenting.

Southwood looks like it did 50 years ago when I left. Street views cached in real estate sites reveal few changes other than the make and model of the cars parked in front of the houses.

Red survived the army. He was the only private in his platoon that knew how to type. Accordingly, he received a clerical assignment and was stationed in Germany.

After leaving San Francisco, I lived and worked in Yosemite for five consecutive years. I rented a cottage near the South Fork of the Merced River in North Wawona for $83 per month.

The End

Building forts, hide and seek. Makes me nostalgic for the good old days.

LikeLike

Holy moly, John. Somehow I missed this earlier. I relish the details, especially the ones I can connect with. I know who Chuck is; I’m laughing over the Pamela reference. I lived on the other side of South City but had a couple of friends on your side of the tracks, er, the El Camino Real. Thanks so much for this. I’m going to go back and read it again. (You bring back many memories: I never shoplifted, but someone once dared me to spread face cream on the shelf of a drug store. My mom relentlessly questioned what the white greasy stuff was on my pants. I had to wipe my hands somewhere. Yes, I was caught and had to apologize.)

LikeLike

Thanks for commenting Janet.

I am pleased to learn you were a bad girl. 🙂

LikeLike

When mom was transferred to the hospital from the County Medical Facility to the hospital, they had a gift shop in the hospital. So I stopped in one day and found a stuffed dog to buy her. When I gave it to her she named it Rex. I never knew where she got that name from, but I bet it was Chuck’s dog she was thinking of.

LikeLike

Thanks Mary. That is an interesting recollection. I have a photo of you and Rex at Christmas time. Funny, isn’t it, how the smallest anecdotes stick with us or can be teased into memory?

LikeLike

Excellent, fabulous recollections of growing up in South City. Although I grew up on Rockwood Drive in Brentwood, we share so much in common, among which is my childhood theft of a Buck Rogers patch off a jar of Ovaltine at the Brentwood Market. I wanted that patch but my mother wouldn’t buy the Ovaltine because I hated it’s taste. So, I swiped it in its plastic wrapper from the top of the jar. I had to go apologize to the store manager when I got caught trying to see the thing to my Girl Scout badge sash. Please continue to write. You are really good at it! Bonnie Tognetti, nee Thomas.

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment Bonnie. Good to know I was not the only petty thief in town. 😎

LikeLike

John, it’s funny. I just wrote a memoir as well—full life actually but my childhood experiences were so similar to yours–especially all the time in Yosemite, where John Ellsworth and I went backpacking for weeks every summer, sometimes with Jeff Jones. l see John and I are going backpacking again in Yosemite in two weeks and I will see Jeff on the drive down. I can send you the childhood chapter if you send me your email. My is jodg@comcast.net. Cheers,

John

LikeLike

Thanks John. I am enjoying your memoir. What a remarkable life you’ve led. Such integrity! Also, I was not aware of our shared love for Yosemite.

LikeLike

OMG, I loved your story of your childhood. You must have known my brother Bill VerBrugge. I will have to ask him about you!—-Vivian VerBrugge Metcalf Brown

LikeLike

Thank you Vivian for the comment. Yes, I knew Bill quite well. We worked together for nine months when I dropped out of college. He graduated from high school with my brother Tom. I liked Bill a lot and he was a good boss and friend to Red and me.

LikeLike

Well done pro. I see a movie in the future. Red must have been a cool guy 😊.

LikeLike

Yeah, sorta. He had a lot of freckles though.

LikeLike

“Norman Rockwell was about to meet Peter Max.” Brilliant line, John, one of so many. I love your writing. Because we are about the same age, perhaps it is not so strange when one thinks of it just how similar our lives were even though I grew up in a small city in northeast Louisiana and you in South San Francisco. Ginger and I are now in Tehachapi and will drive to Yosemite Valley tomorrow morning. I will think about you all the way and all the time we are there.

I am glad that Red survived and that you have come to some reconciliation with the ghost of your father.

LikeLike

Ah yes, the ghost of my dad. Thanks Gary. We share a lot of memories from those days, both in SF and Yosemite. See you soon.

LikeLike

John – I read this over a week ago, a wonderful evocation of those days and the place where we lived and misadventured. Not that long ago I was trying to remember the route I walked from A Street to Southway and this brought it clearly back; a very useful map

Wasn’t nuclear attack one of the reasons for the under the desk drill? Possibly a false memory but nicely ludicrous if it was.

I have no problem at all remembering getting into trouble, including in some of the excursions along muddy stream banks. The window breaking episode is hazier, but somehow think we were following the example of windows being stoned there in previous weeks. We might have taken the rap for all of them. It’s not surprising we were ready for excitement after the Orange Park Rec dances, probably because most of us were too shy to ask girls to dance and we stoked ourselves up drinking too many Cokes.

The other truant behaviour I remember well, although not sure if you were involved, was jumping rides on board the slow freight trains that went past the western side of the park.

Tanforan I knew very well; my father used to work sometimes work there, aside from his regular job, helping to train or condition race horses. When it became a condensed golf course I went there for the only six months of my life I ever played golf, persuaded to take it up by Woo Roberts.

Southwood Market was the location of my only high school weekend job, bagging groceries on Saturdays. Making money to spend up at John’s Men’s Shop or to buy jazz records from Bronstein’s until I decided that free time was more important than that. It would have been a long time after you boosted the yo-yo, of course.

If you haven’t already read it, let me recommend a book to you (thinking about your State College days) titled Fridays at Enrico’s. It’s by Don Carpenter and posthumously published only recently. Quite a bit of it is also set in and around Portland. I’m about to give it an enthusiastic review.

Thanks again for the memoir and telling us the story of your family. I never knew your father was an Okie, as mine was. It’s impossible to think they never once sat beside each other in The Fairway or any of the other serviceable bars of South City, shooting the breeze.

LikeLike

This was great, and I really enjoyed reading it. My favorite line: “… the rickety scaffold of Dad’s youth toppled under the weight of alcohol.” I’m much younger, but your memoir brought to mind the experiences of my late husband’s generation, and those of his friends. Extremely well written. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person